Last updated on May 5, 2020

Introduction – the first-order problem

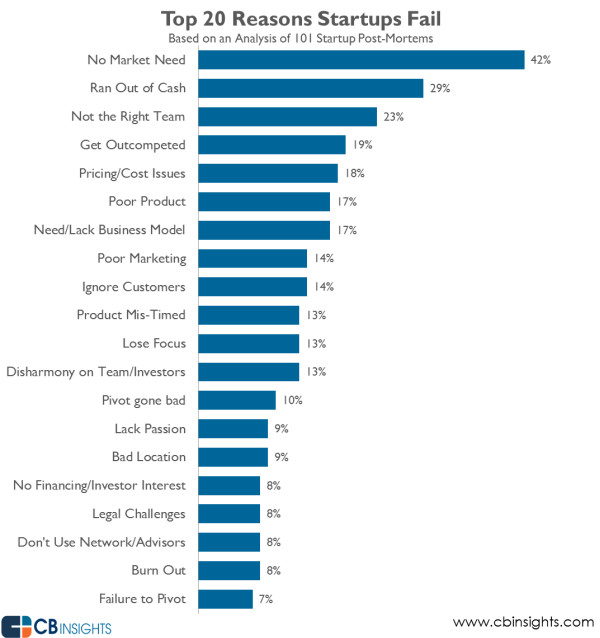

The first-order problem for startups often is, they are not making something people want enough to pay for. As you can see from the CB Insights data, founders identify this as the most common reason for failure.

Figure 1 Reasons for startups failure

Notice the connection between 1 and 2: We can paraphrase that as “there was no market need, therefore the startup ran out of cash.” Investor hype aside (think of Twitter), most startups don’t have the luxury of living years with negative profitability. This is why I emphasise the part ‘enough to pay for’ – contrary to Andrew Chen and others who advice to first get users and then figure out how to make money [1], I’m of the small but growing ‘direct monetization’ school of thought [2].

The solution for this problem is evident: find out from users what they want or need, and then build it.

Second-order problem

But, this is followed by a second-order problem: How should you learn from the users? It’s not evident at all; let me elaborate.

- First, if you ask users what they want, you get inaccurate feedback because the users don’t know all the possibilities. In other words, people don’t know what they want (feel free to insert a Henry Ford quote here).

- Second, if you show them a demo, you get inaccurate feedback because your product is not ready, and the users cannot magically “imagine” how it would solve their problems, if it was ready.

Lean to the rescue?

Eric Ries (video), and a large number of his followers (video), advocate ‘Minimum Viable Product’ (MVP) as the solution. The theory goes that “it’s enough your MVP demonstrates the solution”, as potential customers is shown how the product essentially solves their problem, and for the rest they fill in the gaps. The key difference to a demo is the tight connection to the problem – we only need to show the logical connection between problem and solution (this is referred to as product-solution fit [2]), and for that we necessarily do not need even a laptop.

However, the MVP approach has two major problems. First of all, for many problems you cannot create an effective MVP. Consider Apple Pen, or many other products of that company. “See, here’s a pen – would you use it?”. It’s not very effective – you miss all the subtleties that the final product has and that the people pay for.

Oftentimes, they pay for fine details, not for the hard crude solution. For this reason, the final product often ends up being very different from an MVP which is closer to a prototype.

Second, there are complex problems which have, say, one main problem and two sub-problems. For example, to speeden up the set-up of a manufacturing plant, you need to solve logistical bottlenecks.

But how do you capture that complexity in your MVP? For this kind of problems, it’s all or nothing: a partial solution won’t do.

Moreover, they require the kind of deep customer understanding of the customer’s circumstances which is not usually part of the MVP gospel, centered on simple consumer software products as opposed to, say, B2B industry solutions.

I grant that the MVP approach has advantages, as technically, you could solve a complex problem on a flowchart, or communicate your solution as a video (as Dropbox did). I’m just highlighting that it has shortcomings, too. Most importantly, the final product that the people end up buying is often something very different from the MVP.

So, maybe MVP could be used as a starting point, but not as the end solution.

How, then?

The best solution, as far as I can see, is this:

Learn and much of the nature of the problems, and then bridge that knowledge with the technical possibilities.

As you can see, this approach closely follows Steve Blank’s customer development.

The main difference is that Blank argues strongly it’s “not focus group” (read: market research), in my opinion it’s exactly that. In fact, you can apply both traditional and novel methods of market research to get to the bottom of users needs and wants.

These include etnography, surveys, qualitative interviews, etc. I wrote a separate blog post about market research for startups.

At the core of Blank’s idea is the notion that the founders are testing their hypotheses by customer development. However, those hypotheses originate from innate assumptions about the customer’s reality, and are likely to be biased and flawed.

Challenging the hypotheses is therefore must, and not a bad solution at all. However, we can also start by learning about the problem, not from the hypothesis formulation.

Ultimately, I believe you can reach the same outcome either by starting from the founders’ hypotheses, or by inducing them from market research [3]. Which is faster and more efficient, probably depends on details of execution.

Given the execution is equal, then the accuracy of the original hypotheses is the determining factor — if they are far off, more adjustment has to be done. In comparison, inductive market research, in theory, arrives straight away to the core of the user problems.

Conclusion

In the proposed approach, we take any means necessary to find out what is needed or wanted, and then combine that with the information of what is possible. If you look close enough, this is what marketing is all about – matching supply and demand. Consequently, the role, or competence, of a market researcher, is crucial for a startup organization. They need someone to bridge the technical knowledge, existing in developers’ heads, and customer knowledge, existing in customers’ heads.

Often, these two groups don’t speak the same language, so the individual who is mediating is acting as a kind of an interpreter. (S)he has to have the ability to understand both languages — that of technology, and that of ordinary people.

Notes

[1] It’s the well-known Y-Combinator motto: “make something that people want”. This can be interpreted as getting users being the priority, which is why I like to re-phrase it as “make something that people want to pay for.”

[2] The major exception for foregoing direct monetization is subvention: e.g., in platforms that seems to be the de facto necessity to even enter the market, while for all startup is may be when users are recruited to learn about them. From an economic point of view, this equals subventing one group of users (early adopters) to improve access to another group (main market).

[2] Problem-solution fit precedes product-market fit, which essentially deals with having a product with a lucrative market.

[3] The same separation exists in the academia: There are hypothetico-deductive studies, and inductive studies.

My other writings on startup problems:

- Problem-solution space: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/problem-space-solution-startup-perspective-joni-salminen

- Market research for startups: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/market-research-startups-joni-salminen

- Startup dilemmas – Strategic problems of early-stage platforms on the Internet: https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/99349

- Notes on customer development: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/notes-customer-development-joni-salminen

- The Iznogoud problem: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/startup-syndromes-iznogoud-syndrome-joni-salminen

- The Vishnu effect of startups: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/vishnu-effect-startups-creatorsdestroyers-jobs-joni-salminen